Tl;dr

After reading this blog post, you will know more about these topics:

- Understand the commercial drivers of venture capital term sheets.

- Understand the math behind valuations, investment amounts and how they shape your startup’s future.

- Get to grips with of ESOP/VSOP/PSOP pools and their impact on founders, investors, and employees.

- Know about different share classes, and learn how ordinary and preferred differ from each other.

- Get started with cap tables and know how to model them.

Introduction

Term sheets are a a vital part of most venture capital financing processes. They outline the main terms of an agreement between investors and founders before final legal documents are created. Although most term sheet provisions are non-binding (the few binding provisions of term sheets usually relate to exclusivity, confidentiality and cost reimbursements), they lock-in the basic commercial and legal understanding of the deal and serve as a blueprint (to the lawyers) for drafting definitive legal agreements.

If you are reading this, you have probably already decided that you want to raise money for your company. If you are not there (yet) and want to get to grips with the overall commercial items, consider this guide to seed fundraising by YCombinator for an information-dense kickstart into this topic.

This is a series of two blog articles. In this first part, we’ll delve into the essential commercial provisions found in typical venture capital equity financing term sheets and highlight commercial impacts for each party involved. In the second part, we will focus on the legal side of things and dive into corporate governance provisions and protective measures. After reading this, you will have a better understanding to navigate the term sheet negotiation process with confidence.

Part 1 – Investment Details

Valuation and Investment Amount

Commercially, valuation and investment amounts are the two most important items of any term sheet. You should know that there is no single source of truth when it comes to the underlying math. Although you might be talking about the same numbers, there is quite some room for interpretation when it comes to the exact calculation.

The company valuation can be heavily influenced by nuances. Single words can have a big impact. There are also other, not-so-obvious factors that can heavily affect a founder’s or investor’s stake.

In this section, we will explore the differences and interplay between (i) pre-/post-money valuation and (ii) ESOP pool setup pre-/post round. Each of these items can significantly affect a founder’s or investor’s ownership stake. These examplese are not comprehensive. There are several other possibilities to affect dilution such as the way you convert (multiple) convertible notes before or in a round. I will touch base with these items in later articles that specifically deal with convertible notes.

The industry standard: Investments with a pre-money valuation on a fully-diluted basis

The pre-money valuation refers to the estimated worth of a company prior to receiving any outside investments. It provides a starting point for determining (i) the share price and (ii) the percentage ownership that a new investor will receive in exchange for its investment amount.

Many investments are made on a “fully-diluted basis” (”f-d basis” or valuation based on a fully diluted capitalisation). The valuation on a f-d basis provides a more accurate view of a company’s equity ownership structure and value distribution by accounting for all potential sources of dilution. In other words: It does not matter whether you have issued shares, options, convertible securities, warrants or other potential equity instruments. All of these will be counted towards the capitalisation of the company pre-investment.

The f-d percentage is a commercial number that is particularly relevant for calculating exit proceeds. When it comes to influence the company’s corporate governance, only the actual voting shares are relevant. So, do not forget to keep an eye on the voting shares when you determine investor majority, drag-along thresholds and other corporate governance items.

The f-d percentage is a commercial number that is particularly relevant for calculating exit proceeds. When it comes to influence the company’s corporate governance, only the actual voting shares are relevant. So, do not forget to keep an eye on the voting shares when you determine investor majority, drag-along thresholds and other corporate governance items.

The math to calculate the ownership percentage of a joining investor usually works as follows:

1. Share Price

The share price or price per share (PPS) is the quotient of the pre-money valuation divided by the fully diluted capitalisation of the company prior to the investment. PPS is often rounded to 2-5 decimals, depending on granularity of capitalisation.

Price Per Share (PPS) = Pre-Money Valuation / Fully-Diluted Capitalisation Pre-Round2. # of Shares Issued

The number of shares an investor receives equals the investment amount divided by the share price.

Number of Shares = Investment Amount / PPS3. Actual Investment Amount

To avoid over-/underpayment on shares, many investors then calculate their actual investment amount by multiplying the number of shares with the share price (remember, the non-binding initial investment amount is usually a round number that might not be divisible by the calculated share price).

Actual Investment Amount = Number of Shares * PPS4. F-D Ownership Percentage

Finally, the f-d ownership percentage of the investor is the quotient of the number of shares divided by the fully diluted capitalisation of the company after the investment.

F-D Ownership Percentage = Number of Shares / Fully-Diluted Capitalisation Pre-RoundPost-Money Valuation

In some contexts, investors issue term sheets with a post-money valuation (standard for SAFE instruments, sometimes used in convertible instruments; rarely in equity financing rounds).

Post-money means nothing other than that the investment amount of the round is already factored into the valuation. Here is the formula:

Post-Money Valuation = Pre-Money Valuation + Investment Amount

This approach is more investor friendly. With a post-money valuation, investors determine their ownership percentage upfront based on the total investment amount and the agreed-upon post-money valuation. This calculation takes into account all potential sources of dilution, including existing convertible notes and (employee) options, which ensures that any additional dilution before or during the financing round does not impact the new investor’s stake. As a result, the equity investor has more clarity on the final ownership percentage they will receive.

An investment on a post money valuation basis is considered more investor friendly as it gives the investor certainty on its ownership percentage from this investment. Additional funding from other investors dilutes the existing shareholders / founders.

An investment on a post money valuation basis is considered more investor friendly as it gives the investor certainty on its ownership percentage from this investment. Additional funding from other investors dilutes the existing shareholders / founders.

This is also the reason why post-money valuations are more common in early-stage forward equity or convertible instruments financings. At this stage, some companies need to raise multiple SAFEs/convertible notes before they are able to raise a full equity round. SAFE/convertible investors are not shareholders and, thus, do not have a strong say in the company’s decision making process. For this reason, they often demand certainty on ownership percentage upon conversion.

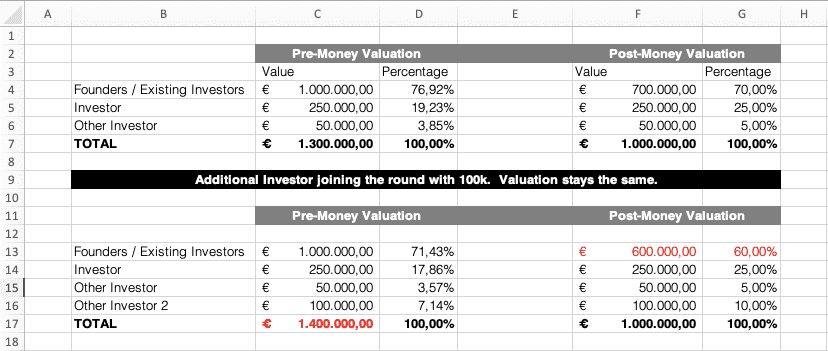

Founders should be aware that a post-money investor does not bear any dilution from additional investors. Dilution is borne by existing shareholders (ie the founders). Consider the following screenshot:

Here are the key takeaways from this scenario:

- The first model shows an early stage financing round with (i) a pre-money valuation and (ii) a post money valuation.

- In the pre-money valuation scenario, the founders and existing investors are diluted by around 23 %. In return, the company receives fresh money from two investors totalling 300k. The new investors recive 19 % and close to 4 % for their respective investment amounts.

- In contrast, if you assume a post-money valuation, the founders and existing investors give up a total of 30 % for the same investment amount. The reason is that the “new money” is already part of the valuation.

- The second example illustrates the potentially drastic effects if an additional investor comes into play and also wants to join the round.

- In the first scenario, a new investor is added “on top” of the valuation. The founders and existing investors still suffer the highest dilution, but also the new investors’ stake is diluted.

- The most severe effects, however, are in the post-money scenario. The dilution is solely borne by the founder and existing investors while the post-money valuation of 1m stays the same.

Pro-Tip 1

To address ever changing round compositions, agree on a total round size at term sheet stage, even when not all investors are known at this stage. This allows for a general commercial understanding while at the same time keeping room for possible additional investors.

Pro-Tip 2

Always be extra careful when the round composition is changing. This can have a quite significant impact on your stake.

Be extra careful when you hand out multiple capped post-money forward equity instruments (eg SAFEs), as this can heavily dilute you before you even have your first priced equity round.

If you want to dive deeper into the commercial factors behind pre- and post-money valuation and how these influence investment rounds, check out Patrick Rogers’ article here, which gives great insight to from a founder’s perspective.

ESOP Pool

An Employee Stock Option Plan (ESOP) or Virtual/Phantom Stock Option Plan (VSOP/PSOP) is a reserve of equity set aside for employees, typically as an incentive to attract and retain top talent. ESOP/VSOP/PSOP pool are typically established at seed stage or increased in subsequent rounds. Depending on whether this takes place pre- or post-investment, different players are affected by its dilutive effect.

ESOP/VSOP/PSOP pools are established/increased either pre- or post-investment, with each option having its own implications on dilution.

Establishing the ESOP/VSOP/PSOP pool pre-investment dilutes the existing shareholders’ equity (eg founders, existing business angels and other investors) before new investors come in.

Setting up the ESOP/VSOP/PSOP pool post-investment leads to dilution of both founders’ and investors’ equity, which can make negotiations more complex (remember, investors like to invest on a fully-diluted basis).

Standard terms for an employee participation scheme include a four year vesting period with a one year cliff along with good/bad leaver provisions. I will get back to this in more detail in the second part of this article series.

Legal considerations: There are two dominant frameworks for setting up employee participation schemes: Real stock and virtual/phantom stock. Real stock refers to the actual shares of the company, which typically provide the holder with ownership and potential voting rights (some jurisdictions also allow non-voting shares).

In contrast, phantom stock is a type of deferred compensation that tracks the value of the company’s shares but does not provide actual equity ownership. It forms part of the company’s fully-diluted capitalisation, but does not show up in the company’s share register. This is the main reason why f-d ownership percentage does not necessarily equal the percentage of voting shares.

The decision on whether an employee participation scheme is implemented by means of real shares or virtual/phantom shares is often heavily driven by local corporate and tax considerations.

In some jurisdictions, real share employee participation schemes are well engrained in corporate law and sometimes even enjoy tax benefits, while in other jurisdictions a contractual virtual or phantom share program is the only way to allow employees to partake in the company’s success.

In my experience, investors and founders should first focus on the commercial aspects of the employee participation scheme (ie pool size, vesting conditions, board approval thresholds for allocations) and rely on the advice from lawyers and tax advisors to implement a well established best practice scheme for the relevant jurisdiction.

If you are in for a deep-dive into the employee stock option rabbit hole, I highly recommend Index Ventures’ guide to stock options for European entrepreneurs. It’s an invaluable source of information and a great reference for every possible ESOP related question.

Share Classes

When you look at financing rounds, there is often a great and confusing amount of different terms flying around. Here is what you need to know:

- Financing rounds are named around the stage of a target company. The stage game works as follows: Pre-Seed → Seed → Series A/B/C etc → IPO. Here you can read more about the specific rounds, but be aware that valuations and round sizes are subject to constant change (ie the Series A valuation from a few years ago is the new Seed by now).

- There are two main classes of shares: Ordinary shares and preferred shares.

- Different (sub-)share classes within a financing round are numbered in sequence.

- As a general best practice rule, lawyers create sub-shares classes for each different share prices that are paid within a round. Different share prices are quite common when you have convertible note holders converting at a discount or cap in the course of a round. In such cases, you may end up with two or more sub-share classes that could be titled Seed 1/2/3 etc Preferred Shares. The underlying legal reasons for this approach:

- Liquidation preference: You want to make sure that every investor only receives a liquidation preference that is equal to their actual investment amount. Specifying the share prices constitutes good practice and avoids ambiguities.

- Amending investor’s rights: Investors usually want to retain control over rights attached to a certain share class within that share class, meaning only a majority of eg Seed 1 Preferred Shares should be able to waive liquidation preferences or board nomination rights for that class.

Now that we got the basics, let’s dive into the legal differences of the different share classes:

- Ordinary Shares, or common shares, represent the standard form of equity ownership in a company. Ordinary shareholders are entitled to voting rights on a one-share-one-vote basis, meaning they have a say in major corporate decisions such as electing board members or approving mergers and acquisitions. Moreover, ordinary shareholders have the right to receive dividends, which are typically paid out of the company’s profits. However, these dividends are not guaranteed and depend on the company’s financial performance and board decisions. Some jurisdictions allow further differentiation, such as non-voting ordinary shares for employees. Unless founders significantly co-found their company, founders almost exclusivley only hold ordinary shares.

- Preferred Shares, on the other hand, offer a “superior” class of ownership with certain preferential rights over ordinary shareholders. In VC backed financing rounds, these often include (note: stay tuned for more detailed information in the second part):

- Liquidation Preference: In the event of a company’s liquidation or exit event, preferred shareholders have priority in receiving their investment capital back before any proceeds are distributed to ordinary shareholders.

- Conversion Rights: Preferred shareholders may have the option to convert their preferred shares into ordinary shares at a specified conversion rate, enabling them to participate in potential upside if the company’s value increases substantially.

- Information Rights: Information rights are regulated quite differently among jurisdictions. In some countries, shareholders can be excluded from receiving information while in other countries, comprehensive information rights are considered core shareholder rights that cannot be reduced. To create a level playing field and a consistent flow of information, professional investors such as VC funds often ask for specific information and inspection rights so that they can meet their own fund reporting requirements. These rights are either attached to a specific (sub-)share class to an investor personally.

- Enhanced Voting Rights: Preferred shareholders may have veto rights or supermajority voting requirements on specific material actions or transactions, giving them more control over significant corporate decisions.

- Dividend Preference: Preferred shareholders may receive a fixed dividend, which is paid out before any dividends are distributed to ordinary shareholders. This offers greater stability and predictability to preferred shareholders, but is currently not very common.

Corporate law aspects: The existence of share classes can either be established through corporate law provisions or contractual arrangements. The distinction has implications for the enforceability of rights associated with different share classes.

In jurisdictions where share classes are recognized by corporate law, the rights and privileges associated with ordinary and preferred shares are embedded in the company’s constitutional documents, typically the certificate of incorporation or articles of association. These rights are legally enforceable, binding on the company, its shareholders and third parties, providing a solid foundation for investors to rely upon.

In other jurisdictions, share classes may not be explicitly recognized by corporate law, and the distinction between ordinary and preferred shares is maintained through contractual arrangements, typically in the form of a shareholders’ agreement. While these agreements can provide similar rights and protections to shareholders as those found in jurisdictions with legally recognized share classes, enforceability may be more complex. This is because contractual rights may be subject to limitations or requirements under applicable corporate law that do not apply to statutory share classes and, as typical part of contract law, only the parties to the shareholders’ agreement are bound by its provisions.

Cap Table

The capitalization table (cap table) is a document that outlines the ownership structure of a startup, including the equity held by founders, employees, investors and convertible/SAFE/option holders. Most cap tables are modelled on a f-d basis. More sophisticated versions also differentiate between f-d holdings and actual voting rights.

The cap table should be updated after each financing round to reflect any changes in ownership. By now, there are several online solutions available that helps the company to manage the calculations and issuance of shares. This is helpful particularly in later stage rounds when a company needs to manage a large number of shareholders and a diverse investor base with several different share classes.

For early stage companies, however, I highly recommend to every first time founder and junior investment manager to not skip the ground work and learn how to model a cap table from scratch. Only then, you are able to fully understand the dilutive effects of different scenarios and can competently adapt to evolving negotiations.

Representations and Warranties

There are books written about representations and warranties (abbreviated also reps & warranties). I am not going into much detail. Here is the super short high-level 101 that you need to know for the term sheet process:

- What? Representations and warranties are statements made by parties in a VC financing round to assure the accuracy of information shared during negotiations. Representations and warranties are different. A representation is a statement of fact; a warranty is a promise of fact.

- Why? Reps and warranties serve to allocate risk, identify liabilities, and ensure transparency between founders and investors.

- Who? It is standard that all parties in a financing round provide reps and warranties. Investors usually provide representations on status and authority (sometimes also as to whether they are accredited investors). The company (and the founders) are expected to give detailed statements about the company’s affairs. Parties that provide warranties are often referred to as “warrantors.”

- How does it work?

- In a representation and warranty regime, the warrantors give several statements about the company’s affairs that typically cover topics such as corporate organization, financial matters, employment matters, intellectual property, material contracts, regulatory matters, compliance with laws etc.

- In addition, warrantors provide disclosure schedules (referred to as “disclosures against warranties”). Such schedules outline exceptions or qualifications to representations and warranties, which can help protect against potential liability.

- If a representation or warranty turns out to be wrong and no exception/qualification was made as to this statement, then the warrantors are in breach and the investor has a claim against the warrantors for the loss sufferred in connection with that breach. To remedy the loss, the investor can often choose between cash remedies or compensatory shares.

Standard terms in VC:

- Warrantors:

- In most European countries it is expected that the company and the founders are warrantors. The reason for including the founders as warrantors is to get them to have „skin in the game“ and to pay close attention to the reps & warranties given (no investor wants to have a warranty dispute in an early stage company).

- In other countries such as the US, however, it is not common for founders to act as warrantors.

- In cases where a company already has an investor base (eg a Series A round), it is not uncommon that also existing shareholders/investors are expected to provide certain reps and warranties. In such cases, they are often divided into “fundamental” and “business” reps and warranties. Fundamental reps and warranties cover topics such as share ownership, title to shares etc and are expected to be given by all shareholders while business reps and warranties are only given by the company and the founders.

- Scope: Reps & warranties become more complex over a company’s lifetime. In a pre-seed round, the catalogue can be quite short, while they usually become longer and more complex in later stage rounds.

- Thresholds: It is common to have de-minimis and basket tresholds. De-minimis refers to a threshold amount, below which indemnification claims will not be entertained. A basket is a threshold amount that must be met before the indemnification claims can be pursued. These thresholds should always be seen in the context of a specific financing round.

- Survival period: The survival period specifies the timeframe during which claims for breach of representations and warranties can be made, typically ranging from 12-24 months post-closing. If there is a follow-on round in this period, then it is often a negotiation item on whether the “old investors” liability regime stays in place for the entire period or is early cancelled to not stack liability regimes on top of each other.

What about indemnities?

While reps & warranties’ purpose is to protect against unknown risks, indemnities allocate risk for known liabilities. For instance: If your investors finds a GDPR leak in the context of its due diligence exercise, the investor will likely ask the company for an Euro-for-Euro indemnification against this specific risk.

Signing Timeline

Often a signing timeline is included in term sheets. This is an approximate schedule for finalizing the investment, including the negotiation and execution of definitive agreements. It’s important that this is a non-binding provision as you do not want a round to go south just because a deadline is missed by a few hours or days.

It is good practice to establish a realistic timeline that allows for investor’s due diligence and negotiation while maintaining momentum in the transaction. In practice, it is good to keep such schedules in mind, but also be open if it takes a bit longer (in most cases, it does).

Valuation, Investment Amount & PSOP put into practice – a real life example

Equipped with the commercial basics, lets dive into a real-life example:

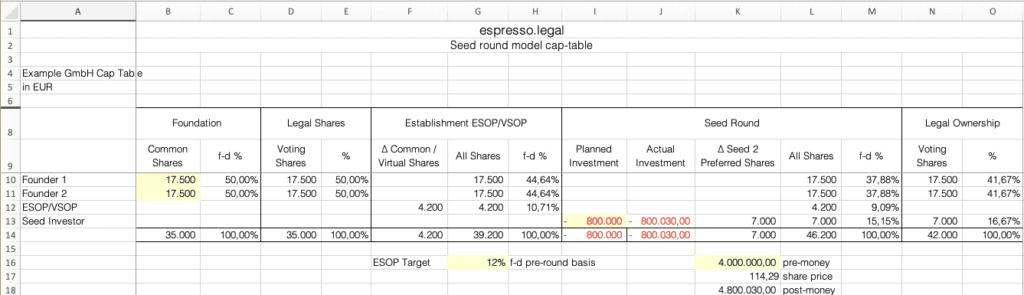

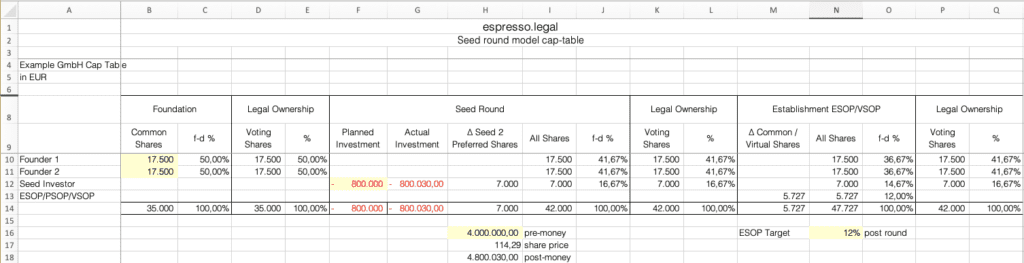

- Consider a seed financing round with a pre-money valuation of EUR 4,000,000 and an investment amount of EUR 800,000.

- Let’s assume the company is an Austrian limited liability company (Gesellschaft mit beschränkter Haftung – GmbH) with a share capital of EUR 35,000 prior to the investment. The company’s shareholders are only the founders.

- The founders and investors agree to establish a PSOP pool with a pool size of 12% of the company’s capitalization (in term sheets, PSOPs are often described as percentage of a company’s f-d capitalisation).

Using a fully-diluted basis that accounts for all potential sources of dilution and the formulas presented above, the math looks like this:

- Price per share: Pre-money valuation / fully-diluted capitalization = EUR 4,000,000 / 35,000 = EUR 114.29 (approx.)

- Number of shares issued to equity investor: Investment amount / share price = EUR 800,000 / EUR 114.29 ≈ 7,000 shares (approx.)

- Actual investment amount: Number of shares issued * share price = 7,000 * EUR 114.29 ≈ EUR 800,030 (notice the small difference compared to the planned investment amount?)

- PSOP intermediate steps: Depending on whether you establish the PSOP pre- or post round, the math will look quite different.

- Option A – PSOP pre-round:

- PSOP pool size post-round: Existing shares + PSOP percentage = 35,000 * 12 % = 4,200 shares

- Option B – PSOP post round

- Total shares post-round (w/o PSOP): Existing shares + new shares = 35,000 + 7,000 = 42,000

- Fully diluted-capitalsation post round (incl PSOP pool): Total shares / Non-PSOP percentage = 42,000 / (100 % – 12 %) = 47,727

- PSOP pool size post-round: Fully-diluted capitalsation post round – total shares post-round = 47,727 – 42,000 = 5,727 shares

- Option A – PSOP pre-round:

- F-d capitalisation of the company post round:

- PSOP pre-round: fully-diluted capitalization pre-round + number of investor shares + PSOP pool = 35,000 + 7,000 + 4,200 = 46,000

- PSOP post-round: fully-diluted capitalization pre-round + number of investor shares + PSOP pool = 35,000 + 7,000 + 5,727 = 47,727

- Investor’s f-d ownership percentage:

- PSOP pre-round: Number of shares issued / new fully-diluted capitalisation = 7,000 / 46,000 ≈ 15.15 % (approx.)

- PSOP post-round: Number of shares issued / new fully-diluted capitalisation = 7,000 / 47,727 ≈ 14.67 % (approx.)

- Investor’s legal ownership percentage (phantom stock is disregarded):

- PSOP pre-round: Number of shares issued / (fully-diluted capitalization pre-round + number of investor shares) = 7,000 / (35,000 + 7,000) ≈ 16,67 %

- PSOP post-round: Number of shares issued / (fully-diluted capitalization pre-round + number of investor shares) = 7,000 / (35,000 + 7,000) ≈ 16,67 %

Now, this might seem a bit confusing at first. Take a look at the following cap table screenshots that illustrate the above example more vividly:

PSOP pre-round:

PSOP post-round:

Here are the key takeaways you should remember from this scenario:

- The total pool size is affected by whether the PSOP is setup pre- or post round (be careful with the wording; I have seen term sheets that refer to PSOPs being technically setup pre- round, but the percentage of the pool size is anchored post-round resulting in a post-round setup).

- With 5,727 shares, the pool is larger by 1,527 shares or approx 35 % in the post-round scenario than in the setup pre-round. This is because the post-round setup factors in the shares that are issued in the course of the round.

- The number of shares issued to the investor are unaffected by the PSOP and is 7,000 in both scenarios. The reason is that the calculation is based on the f-d capitalisation of the company pre-round (in other words: anchored at 35,000).

- The f-d ownership percentages of all involved parties are affected by the structure.

- Despite the differences above, the post-round legal ownership percentage stays the same because the PSOP is disregarded for legal ownership purposes.

The above example illustrates the commercial effects of a percentage anchored PSOP setup pre- or post-round.

In practice, it is important to keep the big picture in mind. At first, it may seem illogical to setup the PSOP post round because both the founders and the investor end up with a lower f-d stake. However, such setups can make sense in practice when there is misalignment on pool size expectations. If an investor expects a larger pool size than the founders are willing to give, the founders could ask to have the pool setup post-round so that part of the dilution is also borne by the investor.

Final note: This is only one of many factors that can affect the f-d ownership percentages of founders and investors. Other factors include the way convertible note holders are converted in the course of a financing round or work-for-equity programs. In follow-on financing rounds, dilution can stem from issuance of new shares, PSOP increases, further convertibel notes, exercised pro-rata rights, anti-dilution provisions or down-round financing rounds.

Stay tuned for part 2 of this term sheet series …

Sources (possibly credible sources I kind of fact-checked)

A Guide to Seed Fundraising – YCombinator

Term Sheet Templates: Clauses to Look Out for During Negotiation – Toptal

Pre-Money Vs. Post-Money: A Guide To These Key Terms For Entrepreneurs – Patrick Rogers @ entrepreneur.com

Rewarding Talent – A guide to stock options for European entrepreneurs – Index Ventures

Series Funding: A, B, and C – Investopedia

My latest reads / listens

Sam Altman: OpenAI CEO on GPT-4, ChatGPT, and the Future of AI – Lex Fridman Podcast

Quote(s) that sticked to me

“Focus on building relationships with potential investors well before you need their money. When you do start fundraising, you’ll be in a better position to negotiate favorable terms on your term sheet.”

— Elizabeth Yin; blog post “The 24 Hour Rule for Fundraising” (2018)

“Term sheets are important, but don’t obsess over them. Focus on building a great company, and the right terms will follow.”

— Naval Ravikant; podcast episode “The Angel Philosopher” on The Knowledge Project (2018)

Coffee fact

Did you know that your daily cup of coffee might help keep your mind sharp as you age? A fascinating study published in 2020 suggests that habitual coffee consumption could be linked to a reduced risk of cognitive decline, especially in older adults (Source: van Gelder et al., 2020). This means that enjoying a cup of joe might not only perk you up in the morning but also contribute to better cognitive health in the long run.

The research indicates that the various bioactive compounds found in coffee, such as caffeine, antioxidants, and anti-inflammatory agents, may work together to protect your brain from age-related decline. So, go ahead and savor your daily coffee ritual with an added sense of satisfaction, knowing that you might be doing your brain a favor. For all the coffee addicts out there: Remember that moderation is key, as excessive coffee consumption can have negative effects on your overall health. Cheers to a healthier, more alert mind with each sip of your favorite brew!

Disclaimer: While I’m a lawyer, who enjoys re-defining lawyering and operating outside the conventional law firm setting, please always consider that I’m not your lawyer. Nothing presented herein constitutes legal advice or establishes an attorney-client relationship. Blog posts on this website have been prepared for information purposes only. Any information is merely a generalised analysis of certain issues raised by particular events or statutory developments. If you have legal concerns that you wish to have addressed, please contact a lawyer directly so that your specific circumstances can be evaluated. The views expressed in this blog are mine alone.